Week 46 update: The call is coming from inside the house

A story like mine has a bit of a catnip quality for media people and gets me invited to join panel discussions and give presentations. I feel this comes with a responsibility: to be truthful, to not oversell myself or the potential of my example to catalyze change in other radicals and extremists, and to know what I’m talking about. That last one may seem like it should already be covered—I was involved in the Alt-Right since before it even began and through to its downfall beginning in 2017, so I must know the subject of the far right. Right?

Yes and no. I know it in a certain way, and in those ways I know it in depth and often personally. But I involved myself in it out of personal and psychological motivations, picking up on ideas and making contact with people according to my own needs and inclinations. I simply ignored a lot that wasn’t interesting to me or that just wasn’t to my taste, and didn’t necessarily study the background of everyone I met. And of course, the Alt-Right was just one among many, many silos of the global far right. I had limited contact with the others.

I owe it to myself and to those who engage me to speak on the subject to expand and deepen my expertise. That motivation has driven my reading of late. This week I read Cas Mudde’s The Far Right Today, which was published in 2019. Based on all the books on the far right I’ve read, I would say that, if you were only going to read one, it may be Mudde’s, but it could also make sense to read a book that was more of a narrative, maybe having to do with whatever local manifestation of the far right is most relevant to you. But if you’re going to read more than one book, and especially if you are going to go deep into the subject, The Far Right Today is possibly the best starting point I know of. His orientation within time, geography, ideology, and electoral politics is very clear and informed, and from his introduction the reader is prepared to move within the framework Mudde provides and explore particular areas in greater depth. (His reading list at the end is very helpful here.) And he gets it all done in less than 180 painless pages.

His manner of analysis is appealing to me as well. Neither he nor I takes the idea of a silver-bullet solution to the far-right seriously. Instead of attempting to map out comprehensive strategies that are supposed to work like recipes for containing and defeating the far right, it is better maintain crystal clarity about the reality of the situation and about what we are defending. This will be a better guide to thought and action, and in itself will inspire and invigorate others to raise their level of activity and resistance.

One reality to which Mudde repeatedly refers is the extent to which the radical right “is a radicalization of the political mainstream,” which already embraces “[n]ativist, authoritarian, and populist attitudes.” These pathologies run deep and wide, and the levees that we used to rely on to contain them are breaking down. Mudde describes this breakdown within the context of party politics:

For decades, the far right has been externalized, associated with amoral and marginalized groups. By definition, mainstream parties were not populist radical right and did not implement populist radical right policies. This meant that, mostly implicitly, it was assumed that the only challenge to liberal democracy came from outside, not inside, the political mainstream. It is clear that this can no longer be upheld. Many of the immigration policies that have been proposed, and even implemented, by mainstream parties, including of the left wing (e.g. the Hollande and Renzi governments in France and Italy, respectively), are virtually identical to those exclusively proposed by populist radical right parties in the third wave. They are steeped in an authoritarian, nativist, and/or populist worldview, irrespective of whether these mainstream parties have adopted them for opportunistic reasons or have truly transformed ideologically.

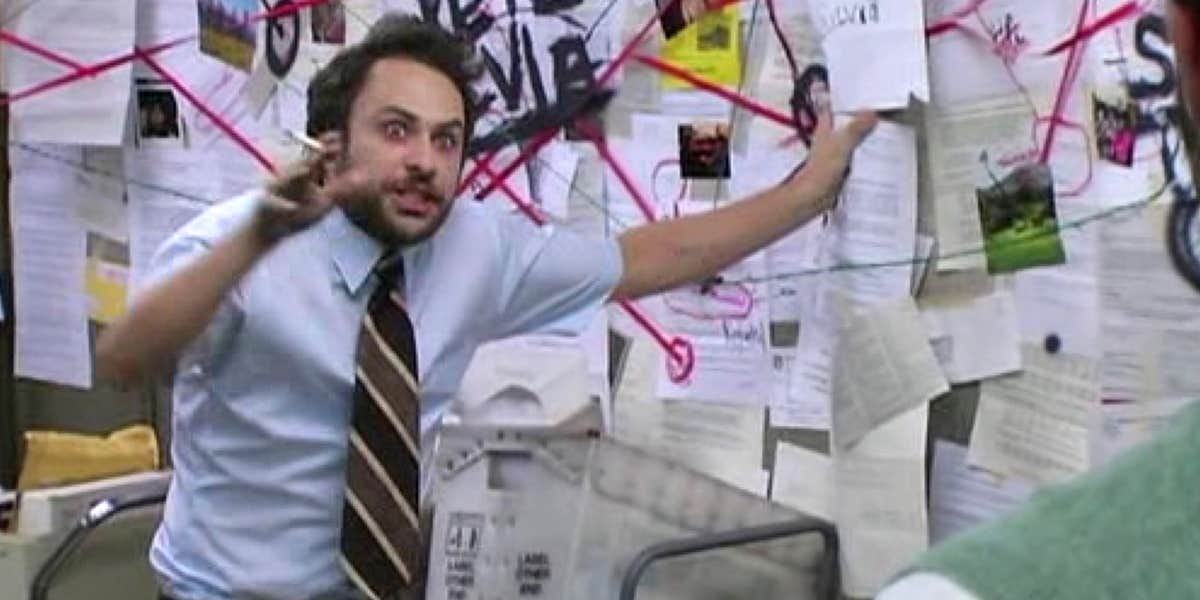

There is a parallel and connected process unfolding in culture and media as well. In the perennial and intenifying struggle in which I am involved—urging participants in public discourse to appreciate the nature and hazard of far right ideas and to strengthen resistance to them—the task is largely to coach people out of prejudices they already carry and that merely await activation by bad actors. The call is coming from inside the house, basically.

Picking up on something I said in my published disavowal of the Alt-Right years ago, Christopher Mathias asked me how I felt about the broader conservative movement. He got my answer: “McLaren said his eventual rejection of white nationalism doesn’t mean he’s now a moderate conservative or Republican. Rather, he told HuffPost, he sees white nationalism and conservatism in America as inextricably linked movements that feed off of and energize each other. (This relationship, he thinks, has intensified since he left the alt-right.)” Pretty much. My experience and observation tell me that the spectrum from conservatism to Nazism is basically a spectrum from crankiness and smallness (conservatism) to hatred and psychosis (Nazism). That’s prejudicial and thrown out from the hip, yes, but it is also my sense of things.

And yet obviously there are conservatives with valuable things to say and insights to offer, and there’s no ideology from the Left that is so complete and perfected that it can dismiss critique out of hand simply because it comes from a more bourgeois direction. Plus, there are some hanging questions at the moment that almost require input from sane conservatives. Like, what, if anything, is left of conservatism after Trump? In his column last week, David Brooks turned this issue on its head:

One of the reasons the Democratic Party is struggling so much is that the radical left ideologies that undergirded its cultural stances are kaput, and it hasn’t yet built a more moderate intellectual tradition to fall back on.

If you want a one-sentence description of where politics is right now, here’s my nominee: We now have a group of revolutionary rightists who have no constructive ideology confronting a group of progressives who let their movement be captured by a revolutionary left-wing ideology that failed.

I don’t fully buy all of Brooks’ premises and conclusions here, but there’s a difference between an argument being unpersuasive to me personally and an argument being so facially wrong that it doesn’t merit a response. I think there are moderated intellectual traditions from the Left that speak to where we are now, but I agree they need rehabilitated and reenergized. One big acknowledgement that I think is missing from Brooks’ diagnosis is how creeps and anti-Semites were always deeply involved in conservatism, even though some of them would be performatively bounced out from time to time, sometimes only partially, and sometimes to be readmitted later.

Brooks is, or has become, a more interesting figure than I appreciated decades ago. I’m struck by his awareness of Sam Francis and appreciation of the man’s coexisting intellectual weight and malignant hate. He is one among a small but growing list of conservatives with whom I want to consult, who have retained their integrity through the MAGA revolution.